A few months ago we covered a very interesting indie horror game currently in development entitled Imperfect. Now that the demo is available, we thought it would be a good time to sit down with solo developer Walter Woods and delve into the process behind the creation of the game.

A few months ago we covered a very interesting indie horror game currently in development entitled Imperfect. Now that the demo is available, we thought it would be a good time to sit down with solo developer Walter Woods and delve into the process behind the creation of the game.

Walter Woods is an independent game developer and professor at SCAD. He comes from a background in architecture and brings that passion and sensibility into his games. Imperfect will be Walter’s second published title.

ROH: Hi Walter! Thanks for accepting our request for an interview.

ROH: Hi Walter! Thanks for accepting our request for an interview.

Walter Woods: Yeah, thank you!

ROH: First off, please introduce yourself and tell us a little bit about yourself.

Walter Woods: I’m from Savannah, Georgia. That’s kind of where I grew up. I was educated in architecture and have a master’s degree in architecture. I practiced architecture in Boston for a number of years. I was always interested in world-building. I think that’s why I got into architecture for the purpose of building worlds, building spaces, and expressing myself through spaces in history, geometry, and light. I really loved that aspect of it. In the practice of architecture, you don’t always get to do that as much.

I was really interested in architectural visualization, which meant that I was using game engines. The new cool thing at that time was to use game engines, like Unreal Engine to visualize your architecture. So, I had a skill set already in the game space. What ended up happening is I met a programmer up in Boston who inspired me and taught me how to code. We started a studio together and just went full-time doing games and VR and all kinds of stuff ever since.

ROH: I always wanted to go to SCAD for traditional 2D animation, but never got the chance. I’m quite jealous. Tell us how you came to be involved with the College.

Walter Woods: It’s a great school. I teach at SCAD now and love it. I’ve always had a studio while teaching, because I just feel like it’s really good for me. I learned so much from development. I bring it to my students. I learn from teaching and bring it to my studio, so it’s a nice reflexive relationship.

ROH: Was SCAD before or after Boston?

Walter Woods: After. I started the studio up in Boston in the early 2010s and went full-time at the studio and started teaching part-time at SCAD. I came back down to Savannah because when you start a company, you want to cut your costs. I did that full-time and was also teaching part-time at SCAD, which snowballed into teaching in the game design department at SCAD, which is what I do now at SCAD. I’ve always kept my studio up. So, it’s been really fun to do both.

ROH: What attracted you to the horror genre?

ROH: What attracted you to the horror genre?

Walter Woods: I write short stories and I’m also a metalhead. I was in a metal band in college and have written a lot of metal songs. I like to dabble in that arena. From a creative standpoint, I’ve always liked the type of themes that you find in those genres, ones that are a lot more aggressive, angsty, or sad. Things like regret, guilt, shame, and redemption. All those kinds of things I’ve always liked to write about and been interested in. Whether I was writing music or writing short stories, or whatever I was doing, I’ve just always been in the aesthetic of horror. I’ve got all these things posted up around my studio that are kind of in that vein.

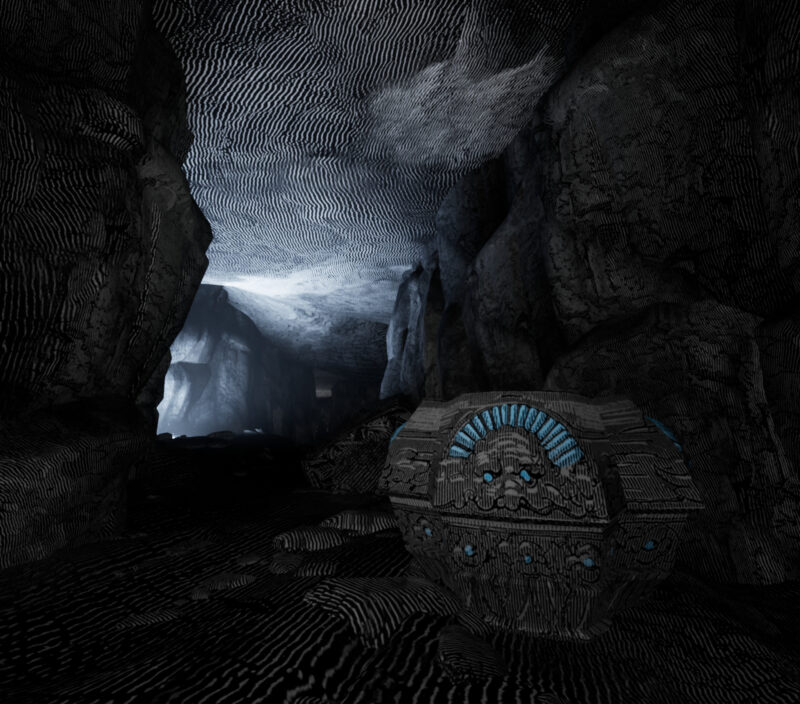

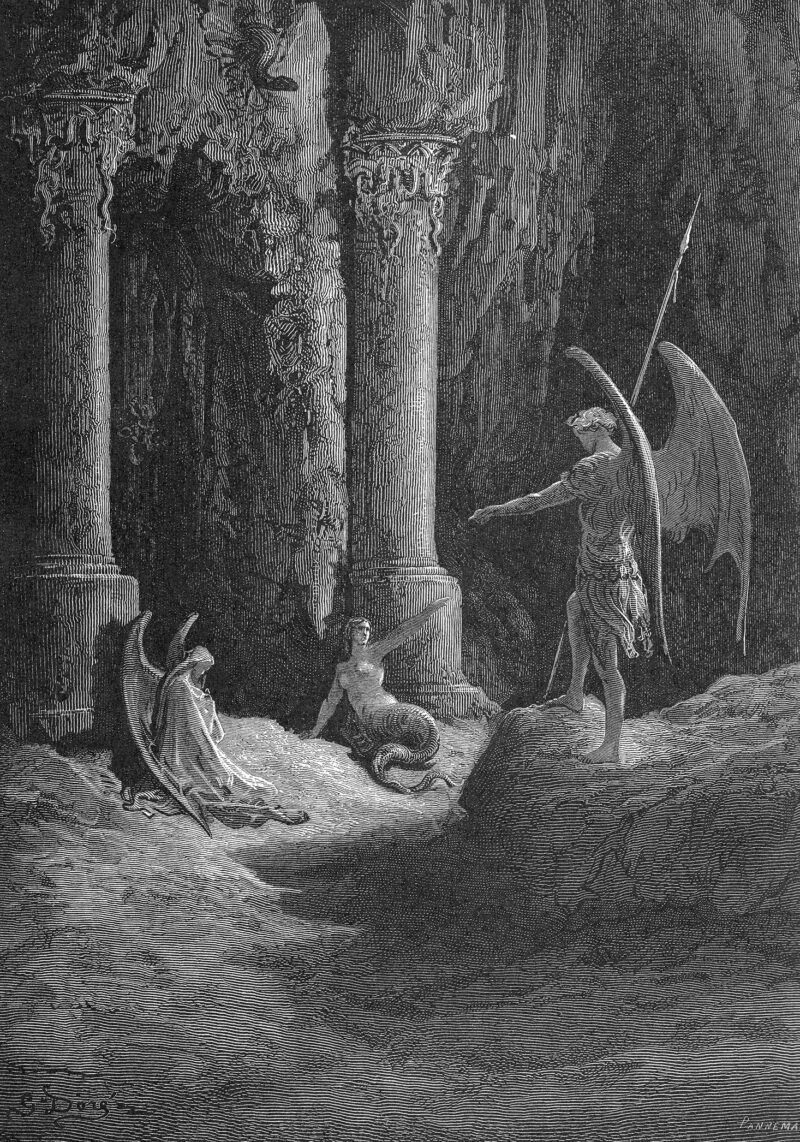

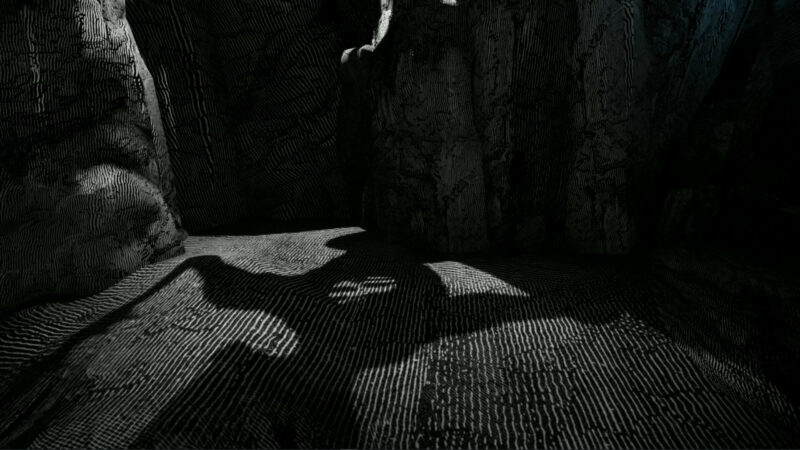

My first game wasn’t a horror game, it was actually a tycoon-style game. I think that I fell into horror because I fell in love with the idea of using the art of French artist Gustave Doré as a way to visualize these themes. It became a really cool way to amplify the ideas that I wrote about with someone else’s creative input. Doré was someone who was amazing at visualizing those concepts. Using his art feels like such a natural fit because Doré was so good at illustrating these themes. The books that he illustrated, like The Divine Comedy, Paradise Lost, or The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, have so many of those themes. I think that Doré and I have similar minds in the way that we think and the kind of themes we connect to.

ROH: Has Doré always been in the back of your head to adapt in some way?

Walter Woods: I’ve always liked the idea of adapting an artist and Doré is my favorite artist. The entire aesthetic of metal albums and metal album covers, it’s just completely him. All of the classic metal, like the death metal aesthetic, it’s all Doré. I have always connected to that super deeply. Throughout school and my career, I’ve been fascinated by history and architectural history, art history, and sculpture and mythology. Doré engaged in so much of that, it was just a natural fit for me.

The story I’m telling is a modern story about these old themes of redemption and forgiveness; the same themes that would be in Paradise Lost. Since this is a story that’s told across history, it’s told so many times and by so many different artists for thousands of years, that using their art to amplify my message is a natural fit.

ROH: I saw the videos where you’re using the scans of the original artwork to make high-res textures for the game. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a developer do that. Maybe they do it here and there, but I’ve never seen a developer use a complete art style to texture their game that way.

ROH: I saw the videos where you’re using the scans of the original artwork to make high-res textures for the game. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a developer do that. Maybe they do it here and there, but I’ve never seen a developer use a complete art style to texture their game that way.

Walter Woods: I have an illustrated Bible by Gustave Doré from 1880 and I use some scans from it for some of the textures and things in the game. A lot of the feel and elements come from here. I use other books as inspiration, but this book was my touchstone for like, “Can it feel like it’s in this?” and trying to connect with people on this visceral level. There’s also a completely practical component to it since I’m a solo developer.

Working with Doré art is like working with the best artists you’ve ever worked with. I get to choose from it like a buffet, which is really fun. I’m really careful about choosing things that I understand, not just appropriating his work out of context. Part of my philosophy around the game is to further the idea of the art, rather than just ripping off an aesthetic without understanding it.

Everything I use, from sculptures to antiquity, all shares themes with what’s going on in the game. For example, use a sculpture called Laocoön and His Sons, which is a Greek sculpture showing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus being attacked by sea serpents. I use the sculpture in the game based on an actual 3D scan of that that exists in the Vatican so that I can express this idea that you’re fighting the serpent at this point in the game. Its inclusion is very relevant. I always try to do that. It’s not just Doré, it’s other artists and sculptors.

ROH: Are there any works by Rodin in your game?

Walter Woods: Not yet. I should get some in there. I use anything that’s appropriate for the theme. I’m not really constrained by the era. If you look at Doré illustrations, especially when he’s illustrating The Divine Comedy, there a lot of historical figures in that book. It’s just a really cool thing to see.

ROH: It’s good to have a strong touchstone like that. I’d imagine it’s a great temptation for a lot of artists to take something because it looks cool, right?

Walter Woods: Right. My students try to do that all the time and it just never works. One of the things I ask them is, “OK, why are we doing this?” Yeah, you’re a great artist and you’re a great mimicker, but are you making something new and recontextualizing? The gameplay mechanic of the frames in Imperfect is literally all about reframing things It’s a fun alignment.

ROH: In one of the making of videos for Imperfect you said you had to tile the artwork in such a way in order to effectively texture map it onto the environments and assets. Can you talk us through that process and the challenge of trying to retain as much of the original artwork as possible while also translating it into a video game aesthetic?

ROH: In one of the making of videos for Imperfect you said you had to tile the artwork in such a way in order to effectively texture map it onto the environments and assets. Can you talk us through that process and the challenge of trying to retain as much of the original artwork as possible while also translating it into a video game aesthetic?

Walter Woods: You can only really pull from one illustration at a time because it’s going to feel like it doesn’t always match. So, for instance, you might have a piece of a brick wall. Typically, any piece of brick that I can find in that illustration, I will try to make that brick wall out of it. Otherwise, I’m just cloned stamping. Sometimes, I’ll very lightly add a little black line to try and fix a seam or something, but I try to use only cloning so that I’m still using all of Doré’s own illustration.

One of the main things that cropped up that I didn’t really think about was the way Doré uses light. When he illustrates something, he’s creating light value across a column, so it’s brighter on one side and darker on another. But in games, I’m relighting everything using the game engine. I can embrace that at times but most of the time, I have to make sure it doesn’t read like his lighting because it’s actually my lighting. That’s one of the things I didn’t expect when I attempted to integrate his artwork into a game, that I would have to neutralize his lighting sometimes but keep it the texture without breaking it. Otherwise, every column is lit from the same direction no matter how it’s turned.

ROH: So, you have to resolve his baked-in lighting from the image.

Walter Woods: Yeah, exactly. That’s a perfect way to put it. I don’t think I’m always successful. I can get better at it. But that’s just one of the hazards of working with someone else’s art that wasn’t designed to be used in a video game. During the process of wrapping a 2D image around a 3D object, I have to make sure I don’t stretch it or goof it too much so that it still retains some of its quality. That can be a challenging process.

ROH: Yeah, you certainly had your work cut out for you when you chose that dynamic.

Walter Woods: I would be doing that if I was working with an artist and having them do illustrations. To me, the payoff is worth it. One of the things missing from horror games right now in my opinion is a unique aesthetic. Mundaun has a really beautiful aesthetic. There are a lot of really nice-looking horror games out there. But are they unique? Probably not many.

We have this sort of scourge of PS1-era aesthetic games. I think people love them, and it makes sense. It’s really l cool because it’s ambiguous. But I think people are ready for something that’s a lot more detailed and lush. That’s what Doré’s illustrations feel like. They just have so much detail and that makes things feel pretty strange. You’re inside this super orchestrated world where everything is predetermined, pre-illustrated, and figured out before you and you’re trying to figure out what the plan is.

ROH: That helps it stand out from the crowd, whether it’s in competition with like a AAA game that’s very detailed, but more photo-realistic or another indie game that’s very low poly or is trying to mimic a familiar retro aesthetic that’s been done before, like the PS1.

Walter Woods: I don’t want to be disparaging of those PS1-era games. I think there are a lot of great ones out there. Don’t make me sound like an asshole but, I just think there’s a lot of room in the genre. That’s one of the great things about horror in general, in film and games, is that it’s super open for experimentation, probably more than any other genre. I love that about horror.

That’s probably why I’ll stay in horror for a while. It’s super friendly to people who are learning to make films and games. Look at the whole Backrooms genre, that’s essentially people learning to make games and people are loving it. They are simple games, but they only have to nail what they’re supposed to nail in order to be successful. That’s a cool thing about horror. You couldn’t do that in any other genre, just tell a simple, small thing and do it well.

ROH: You spoke a little about this already, but as an indie developer what do you think of the current indie horror scene, especially in light of things like The Mortuary Assistant being adapted into other media or taking a game and bringing that into a different space?

ROH: You spoke a little about this already, but as an indie developer what do you think of the current indie horror scene, especially in light of things like The Mortuary Assistant being adapted into other media or taking a game and bringing that into a different space?

Walter Woods: I’ve actually had the privilege to get to know the developer of The Mortuary Assistant, Brian (Clarke) a little bit over Twitter. He’s a super nice guy. Super supportive of indies. Anything great that happens for him, he deserves it.

I think the indie horror scene is really vibrant right now. You can see all these big AAA horror games coming down the pipe after a long drought of big AAA horror games. Usually, if the AAA games are coming in to capitalize on this big vibrant want for great horror, you can tell that we’re doing something right. I think it’d be easy for a lot of indie horror developers to feel threatened by that, but I don’t think it’s the same thing. Those games are going to be great in their own right. That’s from the business standpoint.

From a creative standpoint, I just love how open the horror genre is for indies. I’ve always been a little more of a thoughtful horror guy. I don’t really go for the axe murderers or that kind of genre horror stuff. I like more of psychological horror, so it fits for me. There’s so much space within the genre for that and people love to experience it. Within games specifically, too, it’s really cool, because you really can’t get more scared of anything. A game is going to get you the most scared, more than any movie, because you’re participating in your own demise. You just can’t help it, you know? You’re inside it, you know it’s your fault. You know that if you get killed, or get scared, or something happens to you, you have to participate in order to continue. That’s been fun to manage that.

ROH: And then VR takes it one step further, right?

Walter Woods: I would love to make a VR version of Imperfect. That’s an option in the future. It’s not on the table right now, but I would love to do that if it was something that makes sense. The way that the frame mechanic works means that you have to render what’s in the frame, and then render what’s in the world. So right now, until VR gets a little more performance friendly, I don’t think it’ll work. But, hopefully in the near future, maybe with a new Quest or something, it may be possible.

ROH: I played RE7 in VR and that’s still probably my top VR horror game. My friends and I like to joke that you can’t turn away in that game, because you’re just looking somewhere else inside the game.

Walter Woods: Exactly, you can’t look away at all.

ROH: What are your goals with Imperfect? Are there any unique challenges making this game as opposed to your previous title?

ROH: What are your goals with Imperfect? Are there any unique challenges making this game as opposed to your previous title?

Walter Woods: My main goal with Imperfect was to be a kind of a scope monster, something that I could design and build myself. I’ve hired some contractors to help me with animation and really great illustrator has done some of the illustrations for the game, but most of it is me. I do all the code, all the art, adaptation, and stuff like that. I use some assets for some of them are realistic scenes but beyond that, all the stuff you see is made by me. I also do all the sound recording, the soundtrack, write the music. My friend does the voice of the podcaster in the game, and I write and I record all of that. I just do everything myself. It’s great to have that much control over something but that means that every day you don’t do something, nothing happens. So, it’s all on me, which is fine. I enjoy it. I’ve not yet hated this project. Usually, by now I would hate a project but I have not yet hated this project, which is great. It’s gotten a little bit of attention and people have reached out and helped affirm that it was something worth doing.

But the unique challenge of this project is making sure I understand the art that I use, and that I’m furthering its themes and putting them in an intelligent context. That’s something that I really committed to it. The game design challenge is always at the top of something like this, trying to find the right mechanics that elevate it beyond just a jump scare horror game. It’s not going to be a walking simulator where stuff just pops out of the closet.

Everything that happens in Imperfect that is meaningful and fun and scary in the game, you make happen in a realistic way through the mechanics of the game, through the frames. Once I found the frame mechanic, it all started to fall into place. It took a little while, it wasn’t the first thing I figured out, I had a lot of different options of things that I was trying and testing, but when the frame mechanic came through, it just opened up all these possibilities.

It made sense conceptually and mechanically. It’s a fun mechanic to reveal things and make things scarier because everything’s limited. You can put limitations on it, at times, like making them not be able to use a frame, if they’re crawling through a super-tight space. The horror games that I reference are Amnesia, Inside for the lighting style, and Soma – so a lot of Frictional Games. Those games are so fun because you never lose control of your character. You’re always in that world and not thrown into a cutscene. Everything is revealed from your perspective, and that’s a big challenge. You don’t realize how hard that is, until you’re like, “Oh, God, the player has to actually be able to move around during all of this crazy stuff that’s happening, at least move their mouse a little bit.” And the player has to make the decision to do a thing. As a designer, I can’t just make it happen to them all the time. So, I have to bait them a lot.

ROH: Yeah, that reminds me when Valve was developing Half-Life, they talked about how challenging it was to block the characters and have the scene still play out when you’re 10 feet away on the left or if you’re five feet above, etc. because it’s all told from a first-person perspective and it never cuts away from Gordon Freeman’s point of view.

Walter Woods: Exactly. In Amnesia, they had a technique where they would slightly tilt the camera towards something of interest or spook. I actually built a similar system, but some people didn’t love it. So now, during testing, I’ve made a mode called “Dark mode” where you can turn that option mostly off Because of this, now I have to design the game in mind where people might not get hinted that something’s going on over there. I mean, they are opting in, so if they get lost, it’s kind of on them. So, it doesn’t really worry me that much. But also, sometimes I made the camera look at something cool, and as an artist, it makes me sad if somebody doesn’t see a cool thing I made. But it’s cool, that’s games. People are always going to be looking at a wall while you’re cool-ass cutscene is going on.

ROH: There are always going to be a certain percentage of people that just aren’t going to do what you want them to do.

Walter Woods: I’ve watched enough Twitch streams in this game to realize that just aren’t getting it occasionally, and you’re like, “Oh God, do I fix that, or is this person not smart?”

ROH: Another way developers can lead players to where they want them to go is by using lighting. How much does lighting play in guiding the player in Imperfect?

Walter Woods: Lighting is my number one tool. I use blue light to indicate the importance of various things. I have tools to make sure the lighting is visible at certain distances. That’s something that’s super-important is this grayscale world. It’s not truly grayscale, it’s got colored lighting in it, and I’m usually using that or at least brighter white lighting to help guide the player. After basic level design, lighting is my number one tool. That’s Doré’s number one tool, too. So, it works out. If I’m using his stuff, I make this cool scene that has a specific highlight. That was what he did in every illustration.

ROH: What’s next for you? Do you have any follow-up planned for Imperfect yet? Do you have a lot of ideas that maybe didn’t work with this one that you could apply to the next one, potentially?

ROH: What’s next for you? Do you have any follow-up planned for Imperfect yet? Do you have a lot of ideas that maybe didn’t work with this one that you could apply to the next one, potentially?

Walter Woods: Imperfect is part one of a three-part series. Imperfect isn’t done, this is just a demo that’s out now. The game will be out late next year. So, I have to finish Imperfect, which has got another couple of hours of content that’s coming for it, making the final game two to three hours long. I’m looking at potentially partnering with people to help me finish it and I want to release it widely. The goal is to gain some sort of following for the game so that when I make a sequel people are really interested in it.

The game isn’t going to end in an unsatisfying way. It’s not an episodic game, it’s three independent games. So, I don’t want people to get the impression that it’s an episodic series. But I do have a vision for three sections of the game. The first section takes place in these caves and sewers, where you must use your frames to deal with this giant snake as the penultimate battle of the game. It’s very freaky for a giant snake to be slithering around you and you can only see it through a very small frame. It’s a very unsettling feeling. That’s the big lead up with the first game.

In the sequels, I’ve got more frames, more machines that you use to manipulate your environment, more physics puzzle elements, more types of ways to interact with the world, like crawling through these super-tight spaces. It’s its own mechanic in and of itself and works different than any other game. You really feel claustrophobic; you’re just slightly shoving yourself through a small space. That mechanic comes from one of my favorite horror movies, The Descent. It’s all about delivering on that.

ROH: No one knows they’re there, and now they’re getting stuck in holes.

Walter Woods: There are parts of Imperfect, after the demo, where you’re just like crawling through extremely tight spaces with the rock pressing onto you. And, of course, you’re in there with these creatures and that’s not fun. You start to ask yourself, “Why am I going into a hole that is shaped like a snake? That doesn’t seem like what I want to do.” The next space, featured in the second game, is inspired by Doré’s illustration of these mystical, magical haunted forests. The third game is on the waters, on islands, and on the seas.

ROH: Do you plan on having a new mechanic to go along with each installment?

Walter Woods: New frames. The frames don’t always work the same and some frames can reveal different things, like whole other worlds that are parallel to your world, which gets weird. Stuff like that. There’s also a greater variety of machines because you can just have so many different machines that do different mechanical things.

The design philosophy behind Imperfect is always: “All killer, no filler.” That’s the mantra that echoes in my head. I’ll do a cool mechanic, use it a few times, then move on. I continue weaving it throughout the game, but not to the point where it outstays its welcome.

ROH: That’s really key for horror games.

Walter Woods: Because it’s not scary anymore. It’s the least scary thing ever if you’re just using the same thing over and over.

ROH: As soon as I started getting used to an enemy or a mechanic in a horror game, I’m like, “OK, I know how to deal with this. So, I’m outside of the game and just mechanically playing it. I’m not really scared or engaged anymore.

Walter Woods: The reason Imperfect is more like a movie-length is because you in the game, you kick ass for 10-15 minutes, or maybe 5-10 minutes, and then I throw something else at you. Maybe you start to feel a bit empowered, and then I pull the rug out from under you. That’s what the game is all about, trying to make you feel like you don’t quite have it. There’s no fat. Length is the enemy of fear. If I give the player 20 hours, they’re going to figure out the systems.

ROH: But if you change up the system every four hours or so, you’re essentially making five different games.

Walter Woods: Exactly. I’d rather make three separate games that shift and change. They’ll all have a commonality, and all use the frames, but it’ll be totally new how they’re used.

ROH: Are you using Unreal for this one?

ROH: Are you using Unreal for this one?

Walter Woods: Yeah, Unreal 5. I originally used unreal 4 and I ported it to 5, because I really love the its nanite system, which allows you to use infinite geometry, basically. I’m in a unique scenario where I can bring in a literal several million-poly 3D scan of an amazing sculpture and drop it in. You couldn’t do that with any other engine, you’d have to re mesh it and do all kinds of stuff. So, I love that about Unreal 5.

ROH: Were there any challenges porting the game from Unreal 4 to 5?

Walter Woods: None, it was perfect. It actually fixed a couple of problems I had.

ROH: Oh, yeah? Like what?

Walter Woods: I don’t know whether it was due to my own coding fails or some way that the system worked, but I would look through the frames, and then I wouldn’t be able to see shadows just because of the way my code worked. I assumed there was something I missed. But when I ported it over to UE5, it fixed it, which was amazing. Developers don’t normally have that kind of luck, but I did. It ended up being just fine.

ROH: What programs do you use for modeling?

Walter Woods: I use Maya. It’s a pretty simple workflow. Maya and Photoshop. I don’t even use Substance or anything like that. I wouldn’t say that I’m exactly a game artist. I’m a generalist. I keep my workflow simple. I don’t use weird plugins that other people wrote or anything like that. I just feel like it gets too complicated for me to manage. I’d rather do things than obsess over my workflow.

ROH: You’re not using things that you don’t understand. A recurring theme.

Walter Woods: Yes, exactly. I don’t like feeling dependent on other people, which is probably why I’m a solo dev.

ROH: I totally get that. Was there anything else you wanted to add?

Walter Woods: I’m looking for feedback. I’d love for people to join my Discord. Anybody who wants to test the newer versions of the game past the demo.

ROH: Thanks so much for taking the time out of your schedule to talk with us! We’re all excited about Imperfect. When I first saw it, I felt that it was different in a thoughtful way. It’s something that really pops. It seems like you have a much different approach than a lot of developers have.

ROH: Thanks so much for taking the time out of your schedule to talk with us! We’re all excited about Imperfect. When I first saw it, I felt that it was different in a thoughtful way. It’s something that really pops. It seems like you have a much different approach than a lot of developers have.

Walter Woods: I wanted to try to have a high-concept idea, but real scares and real gameplay. We’re not just walking by reading plaques about why this is interesting. Because at the end of the day, I love this stuff but I think that things are really cool when they have a deeper meaning. Not everyone’s going to access that meaning when they’re playing the game, so it also has to work on the populist level of, “Holy hell, I’m scared! This is fun!” Then the other deeper stuff is there for people who want to dive in.

I really loved it when ManlyBadassHero played my game and all these people were talking in the comments/ Some people are just like, “Holy shit, that’s sweet!” and then others were like, “Oh, is that an illustration from The Divine Comedy? That has a theme of blah, blah, blah, and I wonder if that means this?” There are people who do that. Yeah. There are the theory crafters out there and then there are people who just like it because it’s cool.

ROH: Well, thanks again so much! We wish you all the luck there. Keep us posted on any new developments.

Walter Woods: Thanks so much!

Special thanks to Walter Woods for taking the time to be interviewed and for providing images from Imperfect for use in this article.

Be sure to add Imperfect to your wishlist on Steam. The demo is available now on both Steam and itch.io. You can also follow the game on Discord, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter. Imperfect is currently set to release in late 2023.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.