This year marks the 20th anniversary of the North American release of the original Silent Hill for the PlayStation. Published by Konami and designed internally by a small team known as Team Silent, Silent Hill is a third-person horror adventure videogame which follows a father as he searches through the eponymous American town for his missing daughter. It redefined the survival horror genre and set a bold new standard for how we experience fear in videogames. Upon its release, it was well received by both critics and players alike and was recognized for being an atmospheric, disturbing title that pushed the technical limits of the original PlayStation. It would go on to become a part of the original PlayStation’s Greatest Hits library, selling over two million copies and establishing itself as one of the most iconic horror titles of all time.

Since its debut in 1999, it has spawned multiple sequels, movies, comic books and spin-offs, and has appeared regularly on numerous top ten lists of the best horror games of all time. To celebrate this historic milestone, I’ll be taking a look back at the creation, history and legacy of the first game, to examine just what makes it so special and why it continues to endure to this day. So, grab your flashlight, turn your radio up and keep those health drinks handy, as we step back into everyone’s favorite foggy town.

“Every town has its secrets. Some are just darker than others.”

Pictured: Keiichiro Toyama (director), Akira Yamaoka (sound designer), Takayoshi Sato (CG designer) and Gozo Kitao (producer)

Pictured: Keiichiro Toyama (director), Akira Yamaoka (sound designer), Takayoshi Sato (CG designer) and Gozo Kitao (producer)

Development on Silent Hill began in September of 1996 with an estimated budget of between $3-5 million. The original concept for the game came from the corporate side of Konami and their initial intent was to reproduce the Western success of Resident Evil by creating a game that would appeal to players in the United States. A small development team of 15 people within Konami Computer Entertainment Tokyo, known internally as “Team Silent,” was assembled from a group of employees who hadn’t had much previous success within the company. Consisting of a small group of outsiders with a few failed projects between them, the team was unsure how to realize Konami’s directive of a broader “Hollywood-style” action horror game. As time went on, development began to stagnate and management at Konami began losing faith in the project. Eventually the development team decided to ignore the directives of their higher-ups and opted instead to create a much more psychologically-driven horror game, one which would scare players on an instinctive level. The approach ultimately resulted in a title that far surpassed Resident Evil’s action-oriented, campy style of horror. While never as commercially successful as its zombie-infested cousin, Silent Hill firmly established itself as the gold standard for the genre, with its effects on videogame horror still felt to this day.

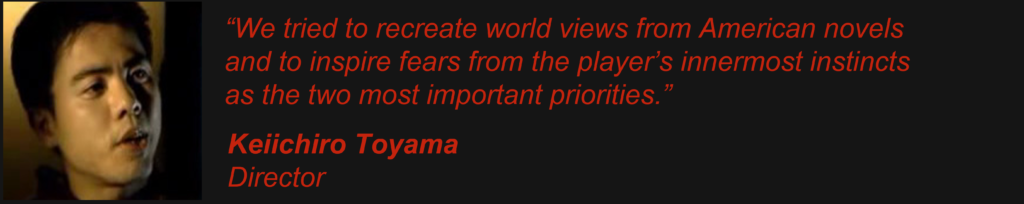

A major defining feature of the game was that it was an Eastern interpretation of Western horror. This concept informed every decision and design implemented in the game. Director Keiichiro Toyama created the game’s scenario, and along with the other Japanese designers, took various ideas and tropes from Western literature and film. They borrowed elements from Stephen King, H.P. Lovecraft, Alfred Hitchcock, David Lynch, David Cronenberg, and Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone, and filtered them through an Eastern point of view to create something familiar yet altogether different. A mashup of all these disparate elements should have felt tired and clichéd, but somehow the game incorporated them in a way that felt completely new, similar to the way in which the original 1977 Star Wars took various elements of mythology, fantasy and science fiction and melded them together to form something fresh. This unique style of interpretation would become a staple for the series.

Anytown, USA

Anytown, USA

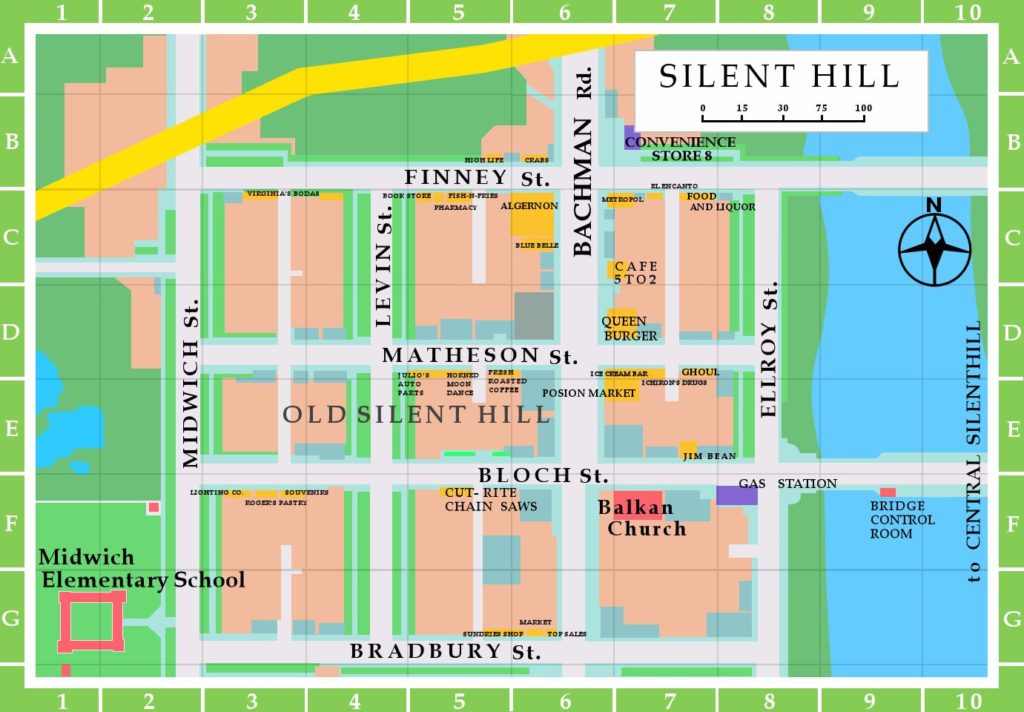

Some examples of this use of familiar elements can be seen in the street names on the town map, which refer to various horror and science fiction authors. Character names and designs also frequently referenced popular characters from films, TV and books. Harry Mason’s original name was “Humbert,” a reference to the main character in Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1962). The name was later changed to Harry, since Humbert was not a very common name in the West. Another subtle reference occurs later in the game, in a scene featuring antagonist Dahlia Gillespie and her daughter Alessa arguing in a dark hallway. The architecture, layout and even the wallpaper is taken directly from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). Silent Hill is littered with such references. They serve as an homage to the past and a recognition of the game’s heredity. The developers incorporated these various references to create a specific Western story.

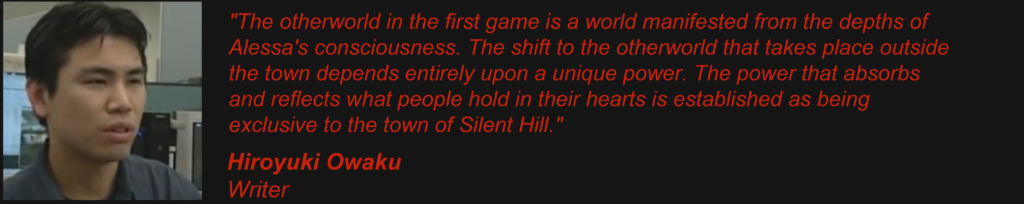

Beyond the many direct referential examples, there are also more substantial Western themes and influences utilized in the game. One such example is the structure of the story itself. In addition to his role as event programmer, Hiroyuki Owaku also contributed as the writer for the game’s puzzles, while character designer and CGI creator Takayoshi Sato assisted with additional elements of the game’s story. The archetype of a Western horror story typically begins with the introduction of “the ordinary world.” This introduces us to the normal world of the characters and provides a baseline for our emotions. Often times the world of the ordinary focuses on minutia and the mundane. At a certain point a shift occurs, transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary or supernatural. This shift could be the introduction of a new character, the discovery of something which spurs a character to action or it could be a first glimpse into a different world. In the case of Silent Hill, the mundane is Harry’s vacation trip to a small resort town.

Things quickly escalate

Things quickly escalate

The developers wanted to make the player feel as if the world of the game existed. They used the general setting of a Midwestern American town as their basis and built the horror on top of it. Chicago was used as one of their Western references, and the team took inspiration from areas close to lakes, since Silent Hill is supposed to be a lakeside resort. The U.S. state the town resides in would later be officially identified as Maine by scenario writer Hiroyuki Owaku. This focus on the real helps players relate to the town as an authentic, tangible place where things work the same as they do in our world – doors open and lock the same way, streets intersect and wind in a natural way, etc. This real-world connection was crucial to the game, because once players believe in the reality of the town, they also believe in the horror.

The introduction of the supernatural happens shortly thereafter with the appearance of a young woman who walks into the middle of the road, causing Harry to crash his jeep. When he comes to, his daughter Cheryl is missing. Things only get worse from there. The town is deserted and snow is falling out of season. Once Harry enters the back alley behind Finney Street, a distant air raid siren heralds a dramatic change. The town quickly transforms into a negative of itself; day turns to night; it’s suddenly raining, and the game plunges players into a world of darkness, decay and rust. This transition is a literal shift between worlds, evidenced by the aforementioned nocturnal switch and geographical shifts from one location to another. The town is also blocked off and characters are unable to escape, due to giant sections of the roads having simply dropped off into nothingness. All of this helps to create a persistent, ominous mood.

Stephen King’s The Mist, a novella about a small town enveloped in an unnatural fog filled with deadly monsters, was a direct influence on the game’s story and informs key elements, such as the setting of the town, the fog and the inexplicable monsters which emerge out of it. The Mist starts off in the ordinary world, with a family’s quick trip to the town’s local supermarket to pick up a few groceries. However, once they arrive, the fog rolls in and the situation quickly changes. Its story also follows a father in his quest to combat supernatural forces to protect his family. While Silent Hill shares a number of similarities with the premise of The Mist, the developers ultimately used it more as a jumping-off point.

Look familiar? A scene from the film adaptation of Stephen King’s The Mist (2007)

Look familiar? A scene from the film adaptation of Stephen King’s The Mist (2007)

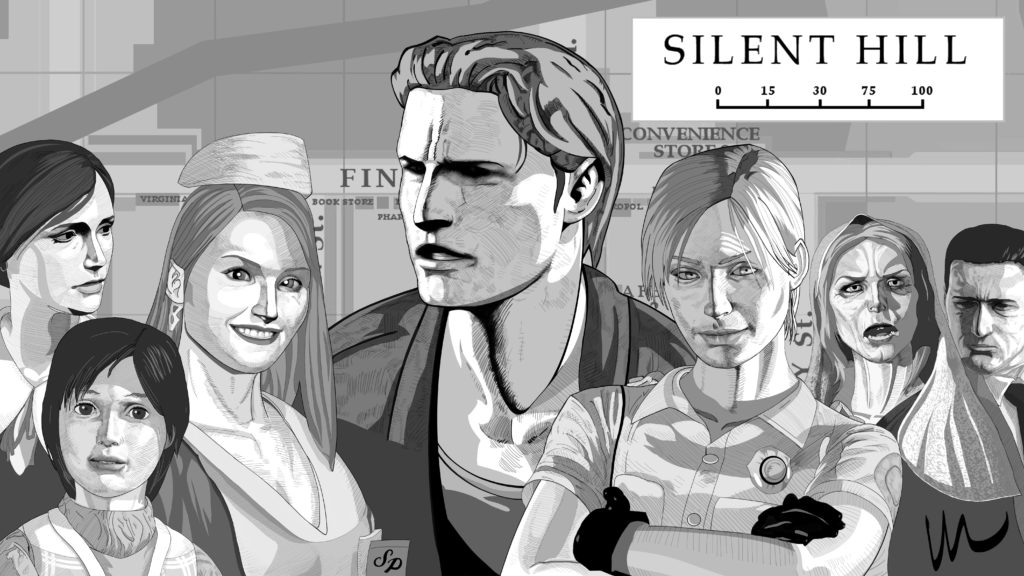

Silent Hill has a simple premise, a father in search of his missing daughter. Harry Mason is an everyman, a neutral character that everyone can easily relate to. He’s also not your typical action-oriented videogame protagonist; he’s an average, everyday guy. Harry is the player. His aim isn’t great. He stumbles sometimes and gets out of breath after running for a while. Aside from Harry, there are only six other characters in the game, but every one of them has a purpose and a specific role to play. They’re all pieces of the puzzle that Harry is trying to solve.

Cybil, a cop from the next town over, aids Harry in his quest to find his daughter. Dahlia is a mysterious woman who cryptically guides Harry to different points of the town, her motives unclear. She ends up becoming one of the game’s main antagonists, along with the duplicitous and self-serving Dr. Kaufmann. Lisa the nurse is a local and provides Harry with info on the history of the town. Cheryl and Alessa are revealed to be two halves of the same soul, split years ago and yearning to reunite. Both characters serve as catalysts for the story. Cheryl wanted to go to the town and Alessa caused Harry to crash his jeep, both events drawing these characters closer to the town. Through these characters Silent Hill explores the nature of loyalty, corruption, innocence and duality to name a few.

As with most of the game, much of the character development is beneath the surface, encouraging players to dig deeper to understand their various motivations. Even though the game is largely plot-driven, many of the details are in the background. The developers provide a general framework to hang the story on, but much of what happens is subjective. Players enter the town knowing very little. By the time they leave, they have some answers, but many of the bigger mysteries are, for the most part, left unresolved and largely open to interpretation. This allows the player’s imagination to fill in and shape the details. The game has a total of five different endings, each with its own set of consequences based on the player’s actions. Specifics are oftentimes left purposely vague and ambiguous, a hallmark of the series. This is yet another example of simplifying the structure to streamline its effectiveness.

Even as the game filters Western themes and ideas through its cultural consciousness, it still retains distinct elements of Asian culture and tradition. One of the major cultural differences between Asian and American horror is the structure. In the West, the structure is typically direct: we discover something supernatural is going on; we figure out what it is; and we figure out how to solve it. In Asian horror, the supernatural is something much bigger than we are. There is no defeating it. In traditional Japanese ghost stories, tragedy, suffering and loss all feature prominently. Ghosts are often born out of a rage brought about by some traumatic event, like murder or suicide. This trauma marks or stains a place, creating a curse. Asian horror is also subtractive, characterized by its minimal use of elements to inspire fear. It relies more on suggestion and suspense, rather than gore and violence. Stories are more open-ended, and there is typically less explanation about what’s happening. There’s rarely much closure either, just like in real life. In the game, crucial details about the characters and plot are withheld, and even though Harry is able to escape the town with a new form of his daughter, the question of why Silent Hill is the way it is, is never answered. These are just some examples of how various elements of Eastern horror are woven into the game.

Keiichiro Toyama (above center), producer and director; Akira Yamaoka (above left), composer and sound director; and Takayoshi Sato (above right), character designer and computer graphic artist

Keiichiro Toyama (above center), producer and director; Akira Yamaoka (above left), composer and sound director; and Takayoshi Sato (above right), character designer and computer graphic artist

Another major defining trait of the game is its emphasis on psychological horror. Plenty of other games before Silent Hill had dabbled in the horror genre, most notably on the PC. Beginning with Alone in the Dark (1992), a handful of other games, including some text adventure games, H.P. Lovecraft adaptations and Phantasmagoria (1995), explored various aspects of the genre, with varying degrees of success. But the closest console games ever got was a more action-oriented approach to horror, in games like Konami’s own Castlevania (1986) and the TurboGrafx-16 gorefest Splatterhouse (1988). Some notable exceptions were Sweet Home (1989) on the Famicom and Uninvited (1991) on the NES, which both placed an emphasis on story and atmosphere. It wasn’t until the next generation of 32-bit consoles that developers had the technical means to effectively explore psychological horror in videogames.

Silent Hill was one of the first earnest attempts by game developers to get to the root of what horror is. Character designer Takayoshi Sato said the team didn’t want to do anything too obvious and avoided shallow illustrative monsters or atmosphere. They carefully chose designs and scenarios which were ambiguous and chaotic, ones which could generate twisted images in the minds of players. The developers also frequently betray player expectations. When players expect something to jump out and scare them, nothing happens, and vice versa.

Monster and background designer Masahiro Ito designed the creatures that inhabit the town in an abstract, often amorphous style, giving players just enough detail to let their imaginations and subconscious wander. Ito drew inspiration from the works of British figurative painter Francis Bacon and infused his own designs with a similar organic, fleshy aspect. Grotesque creatures such as skinless dogs, pterodactyl-like air screamers, child monsters and others, all populate the town and terrorize the player in different ways. Silent Hill, both the game and the town, excels at creating this type of abstract terror. In the uncertain space of our imaginations, we can insert everything that terrifies us. Everyone’s fears are different, and the deliberate choice to let the player’s imagination mold the game and customize it to whatever fears each player has was innovative and inspired. This core concept of exploiting the abstract helped set the game apart from its competitors and is one of the main reasons that it endures today.

Simple but effective

Simple but effective

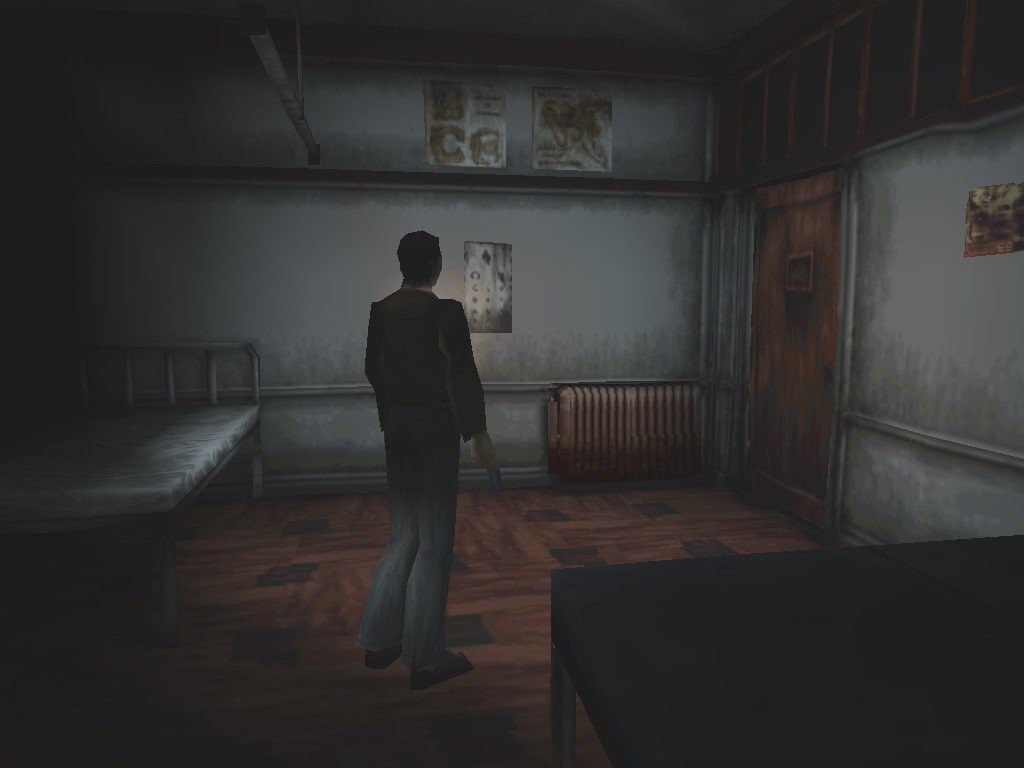

Advanced for its time, Silent Hill pushed the graphical limits of the original PlayStation. Characters, objects and environments were designed using a limited number of polygons to create simple, but recognizable forms. The same way the cubist art movement simplified three-dimensional forms into abstract representations for expressive effect, Silent Hill’s polygonal graphical style helped to define the visual language of the game by representing its subject matter as simplified 3D models, further advancing the abstract aesthetic of the game’s overall design. One of the ways the game’s graphics differ from its contemporaries is by using a dynamic moving camera and real-time 3D environments, as opposed to the static, pre-rendered backgrounds of Resident Evil. This enables a greater degree of player agency and makes for much more dramatic presentations.

The fog which covers the entire town is one of two critical visual elements in the game. It limits the player’s field of view and obscures details around them, which helps to build suspense. Since players can’t see very far in it, they never know what’s going to jump out. The inclusion of the fog was partly a result of the game’s engine not being able to fully render the expansive surrounding environments. In addition to adding to the game’s ominous atmosphere, the designers also included it as a way to mask the technical limitations of the PlayStation’s hardware. The creative byproduct of this technical compromise was that it significantly enhances the mood of the game. It would go on to become the single most defining iconographic feature of the series.

The other critical visual element of the game is the flashlight, which serves a similar gameplay function as the fog. The majority of the players’ time is spent alternating between light and dark. Depending on the area, they’re either enveloped in fog or darkness. One of the essential items they have to aid them is the flashlight, which can be turned on or off. Players rely on it to see where they’re going, but it only illuminates so far in front of them. It can also be a liability, since it can attract nearby monsters. Since players can’t see very well to begin with, the flashlight highlights when something actually does appear. This dynamic emphasizes the element of suggestion and creates anticipation and expectation in the game, ratcheting up the player’s tension.

Even though the game’s focus is on psychological horror, it doesn’t shy away from weapons or combat either. Harry is armed with a diverse mix of melee weapons and firearms to combat the evil creatures that stalk through the town. Combat is broken up by a number of cerebral puzzles. In addition to discovering general details about the town, players can also inspect the environment for clues. Oftentimes riddles or environmental puzzles require the player to manipulate an object or system in order to obtain an item or proceed forward. Frequently these puzzles involve everyday items like pianos and water drains, further reinforcing the idea that the town, and the logic behind it, is based in a real, believable world. Puzzles regularly relate to the story and ensure that the game isn’t just a mindless hack-and-slash affair, without any substance.

There’s blood on some of the keys…

There’s blood on some of the keys…

One of the gameplay conventions Silent Hill retains from its predecessors is the third person “tank” control scheme, named for its rigid steering mechanics. The majority of 3D survival horror titles of the time featured this distinct setup. Movement in this control style happens relative to the position of the player character, as opposed to the position of the game’s camera. For example, pressing “Up” on the controller’s directional-pad moves Harry forward, regardless of which direction he’s facing. While some players find this setup to be clunky and cumbersome, others can easily acclimate to it and appreciate the consistency of being able to easily maneuver their character around, regardless of changes in camera angles. Some believe it adds to the tension of the game, while others think this “challenge” is simply an artificial result of the clunky mechanics.

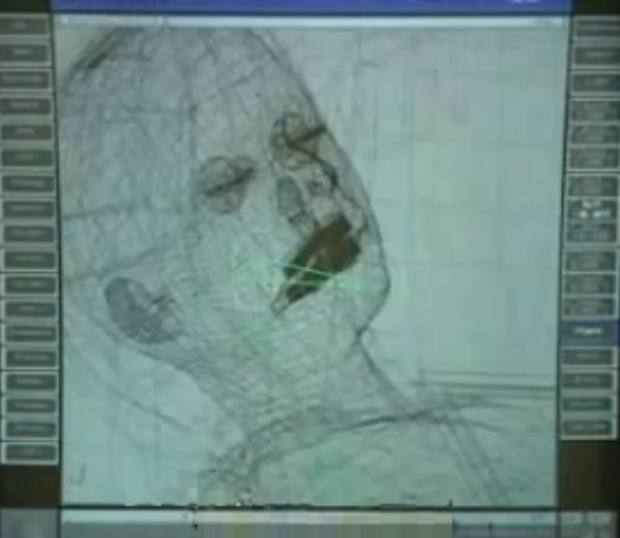

Character designs and cutscenes in the game were created by Takayoshi Sato. He was also responsible for the creation of the environmental modeling, texturing, animation and lighting. Sato didn’t think players would be afraid of typical “scary” designs. Instead, he utilized two main factors that evoke players’ fears to help him in the design process: first, was the concept of players seeing something beyond their understanding; and second, to see concealed their true-selves. He applied these ideas to help govern how the visual language of his designs would reflect the world of Silent Hill. His character designs covered a wide range of facial and body types, from young children and elderly characters, to tall male figures. He took extra care to create visual signatures for each of the characters, such as the withered neck of Dahlia Gillespie. The reason why some of the characters resemble Hollywood actors like Bill Pullman, Cameron Diaz and Julianne Moore is because Sato didn’t have Caucasians models for determining specifics like skull shapes, etc. and often times used images of Western actors as a reference.

A wireframe model of one of the Sato-designed characters

A wireframe model of one of the Sato-designed characters

Sato completed all of the game’s award-winning pre-rendered CGI cutscenes singlehandedly and without any staff assistance. This wasn’t by choice, however. He had to do it in order to get credit, since his boss at Konami was reluctant to credit such a young employee. The personal cost of such a monumental task was substantial. According to Sato, for one second of a cutscene, it took about three to four hours of rendering time. After all the employees had gone home, he used the computing power of roughly 150 workstations to render his work. In total, he spent almost 3 years working on the game. Perhaps no other single creator can be said to have had as much influence on the look of the game than Sato had. His work established the foundation for how characters would look in the series.

No retrospective of Silent Hill would be complete without mentioning the game’s groundbreaking use of sound. Silent Hill doesn’t just manipulate players’ emotions by what it shows them, it also manipulates them by what they hear. The sound design and music may just be the most distinctive quality of the game. Perhaps more than anything else, it affects the players strongly by establishing a singularly dark and ominous tone.

Both the soundtrack and sound effects were produced by Sound Director Akira Yamaoka, who had requested to join the development team after the original musician left. Yamaoka’s use of harsh industrial sounds blurs the line between sound effects and a traditional score. As players navigate the twisted underworld of the game they’re never sure whether that loud clanging noise they hear is happening inside the game or whether it’s just the soundtrack, further reinforcing the game’s overall ambiguity. Other ambient sounds, like persistent low pulsing and humming tones, which are heard throughout most of the game, add to the unrelenting nature of the dark, omnipresent atmosphere. From the dissonant cacophony first heard in the opening alleyway section to the violent staccato crescendo it reaches when battling the Incubus boss at the end, the sound assaults your senses and amplifies the terror. The soundtrack covers a broad range of musical styles, from haunting synth melodies and string arrangements, to experimental ambient compositions. The game’s opening mandolin theme and melancholy end piano theme are just two of the many tracks that are burned into the consciousness of countless players. The soundtrack would later see a release on CD, and more recently, a vinyl version.

Just as the fog and flashlight are critical visual elements in the game, a critical auditory element was the radio, which emits static whenever monsters are near. The player finds it early in the game and it quickly becomes a critical resource. It acts as a kind of radar or sonar device; the closer the monster, the louder the static. So, even though players don’t actually see the monsters, they still feel their presence. The radio is a key feature which ensures players never feel at ease, even in areas where there’s no visible threat.

Another iconic sound from the game is the air raid siren. It is first heard in the alleyway, when Harry chases after Cheryl, following their car crash. It heralds the transition between the ordinary world and the Otherworld. It’s a warning to players, establishing that a dramatic change is imminent. This recurring sound effect elicits a reflexive response of alarm and dread every time the players hear it. They know that even though they haven’t heard it in a while, it’s never very far off and they’re never truly safe. It also helps to effectively punctuate different sections of the game. It became another trademark of the series, sending a chill down many a player’s spine.

Silent Hill was released during a time when voice acting in videogames was still finding its groove, especially regarding English-speaking actors in Japanese titles. It was an awkward phase. Using professional voiceover talent in their games wasn’t a major priority for most developers. As the first console generation with the capability to feature full in-game voiceovers, 32-bit games suffered the most from a large number of subpar performances. Standards in quality were all over the place.

Resident Evil became notorious for its exaggerated, cartoony deliveries, while games like Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver and Metal Gear Solid used professional actors and were recognized for their quality voice work. Silent Hill fell somewhere in the middle of this spectrum, utilizing a combination of talent with varying degrees of technical expertise. Performances were delivered in a dreamy, surreal style, with dialogue punctuated by deliberate pauses between each line. According to professional voice actor Michael Guinn, who played Harry in the game, the decision to have the roles acted in this affected style came directly from Konami, not the professionals who worked as voiceover actors on the game. He went on to say that the weirdest thing about his performance was that he wished that he would’ve been allowed to act more naturally, but acknowledged the distinct quality it gave the game. Some have called the voice acting stilted and distracting, but others believe those performances contribute to the game’s charm and simply see them as a part of the language of the game. The town and just about everything that takes place in it exists in a skewed, warped version of reality. It only makes sense that characters would also sound and act differently. While this may not necessarily have been the original intent of those involved, it nevertheless informs the game’s story and tone, and stands out because those performances are not normal.

CLOSING THOUGHTS

Videogames are not passive experiences. They’re immersive. They draw players in and demand responses. A horror game is something unique. It dares players to survive it. It challenges them in ways other games simply can’t. It doesn’t matter that players sometimes play the game in the middle of the day; inside the game it is night, and they are nervously navigating a dark, rainy alley. Surviving this digital crucible is a kind of rite of passage. Just like Harry, players have to go through hell to finish it, and, when it is finally over, they feel elated.

Silent Hill is a masterpiece of horror that has stood the test of time and remains as potent and relevant today as it did when it was first released. The same way good stories are timeless, effective horror will always be scary on some level. Even though players might be able to predict when a corpse is going to burst out of a locker or when a dog is going to jump out of a blind alley, the things that truly terrify them remain embedded in the marrow of the game – the sense of dread, fear of the unknown, and the darkness of their own minds. Real horror leaves a stain.

Even though the series has fallen by the wayside, its relevance has not. Its legacy endures and continues to influence such popular modern titles as Outlast, Remothered and Lost in Vivo, as well as popular film and television, with Stranger Things co-creators the Duffer Brothers referencing Silent Hill directly as one of the show’s main influences. There are more horror games out now than ever before. It’s a new golden age. Just as the fog that perpetually covers the town itself, Silent Hill’s influence lingers and refuses to dissipate. It forever changed the face of videogames and has left a permanent mark on the landscape of survival horror. For this and many other reasons, it remains a horror classic.